In Theory...

To give you the gist of his philosophy, our current grading system is antiquated. It has been grandfathered in and we all do it because, well, we don't know of any other way! And a lot of other stakeholders rely on it (colleges, in particular). Changing what we do requires a lot of education--of our students, their parents, administrators, and (if we were going to make a true systemic change) the general public.

We live in a world obsessed with grades. Too much emphasis is put on grades at the expense of actual learning. We (students, teachers, parents, administration, the government, colleges, etc) care way too much about the product and not enough about the process. Students get one shot and everything counts. They can't learn from their mistakes because they are expected to get it right the first time. This results in what Kevin calls "neural downshifting." Students don't feel safe to fail. so they retreat to the safest, easiest option. This often means cheating, but even at the most innocuous level it means just doing the bare minimum required to get a certain grade.

Kevin brought up the book Drive by Daniel Pink, which talks about motivation. In Drive, they look at how likely a person is to complete a difficult task based on how much they may or may not be paid for the task. For more complex tasks, motivation to complete the task actually decreases when a monetary value is placed on completing the task. Perhaps this is because once you assign a monetary value, the person makes a judgement about whether the time involved in completing the task is worth the reward they will receive. Without money in the picture, the task completion becomes about satisfaction with solving the problem as opposed to reward for solving the problem. Not only that, but an external reward tends to stop working the moment it is taken away. Grades often work the same way. Kevin conducted an informal interview with a variety of students and they all were on the same page about this idea: they are much more engaged and happier with a task when they are doing it with a purpose other than to get a certain number of points.

Another huge problem with our current grading system is that it is completely subjective. We are sold the illusion of objectivity in grades, but when you get right down to it, it is not all that objective. So many factors come in to play--weighting of materials in class, what is graded by the teacher and how, how much emphasis is put on certain grades, what counts and what doesn't--there are just way too many variables to create a level playing field. We can come closer to being more consistent from class to class, but we will likely never have a completely level playing field.

Think about this: suppose you were on a college admission panel and you were looking at grades. You saw that a certain number of students all got an A in a particular biology class. They all came from different states and different schools (or maybe even different teachers within the same school). Does that A really mean the same thing for each of those students? Should it? Do we tend to believe it does? All of these questions are not necessarily easy to answer (you would probably have to ask many more follow up questions to really get at an answer) and that just goes to show how varied our grading systems really are.

Along these same lines, the true score theory also comes into play. For any particular grade given, it is a combination of factors which include both true ability and random error. Assessments are a measurement, and for every measurement there is going to be some level of error. Sometimes an observed score is very close to the true score but sometimes it is not. So every grade reported (based on a particular teachers' grading scheme) will include a certain amount of error (ie plus or minus 4%). This adds another layer to the loss of meaning in a grade. Not only is it subjective, but within a framework of subjectivity there is that extra layer of error. Combined, these result in a significantly imprecise and inaccurate grade.

Our grading system also works as a deficit model, essentially everyone starts at 100% and we take points away. Our grading scale therefore sets students up for a cycle of failure after one mistake. A student can have an issue early on in a semester that sets them significantly back for the rest of the semester. They could be in a hole that they cannot possibly dig themselves out of. Notice the average score of each student below. I have created a graph of the grades for the first 3 students over time, which you can find below the table.

Source: http://hirschda.blogspot.com/2013/11/heres-whats-wrong-with-averaged-grades.html

You can see that even though each of these students end up with the same 79%, their actual grade progression shows very different stories. A grade doesn't have to be an average. This is the thing that causes the most issues for students who have either one bad grade or a series of bad scores and then they are in a hole that they can't get out of. A grade should be a measure of central tendency to mitigate those outliers. When averaging, outliers have a huge impact (could be positive or negative) and will not really show a student's true understanding necessarily. This comes back to the idea that learning is not fixed, that growth can occur and it should be reflected in a student's grades.

Zeros are particularly damaging in grade calculation. Notice students 6 and 7, who achieved near perfect scores throughout the semester, but each also got one score of zero. This brought their average down tremendously. Also, think about the student who starts out with a zero or two. Right off the bat, they are in a hole that is hard to get out of. Their chances of achieving an A in that class are dramatically reduced. Even if they work very hard and do very well for the rest of the semester, their score is tainted by that zero. Part of the problem is that scores of zero just don't make sense on a hundred point scale. I could not do as good a job of explaining this idea as Rick Wormeli can, so I have provided the video below for you to get a feel for the reasoning behind this concept (I think I saw this for the first time in Kevin's workshop a couple of years ago).

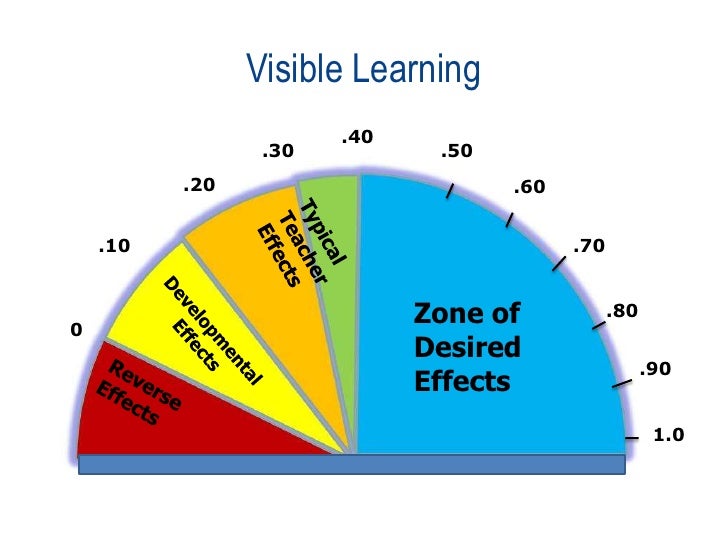

Kevin referenced the book by John Hattie, Visible Learning. It is basically a meta-analysis of multiple meta-analyses and is apparently very dense. But I have often heard of it referred to when learning about various practices and their "Effect Size" on learning. Basically, the idea of Effect Size is that there are certain effects that are inherent to a students development and just being in the room with a moderately effective teacher. You can get an effect size of about 0.4 just from putting a student in school. (see below, "Typical Teach Effects") There are a few things that have a reverse effect, like retention, a student moving schools a lot, and excessive TV watching. But here are the things that Hattie found to have the greatest effect sizes:

1. Students know what they are expected to learn.

2. Students know what successful learning looks like.

3. Students receive timely, specific feedback for where they stand.

4. Students can define where they stand relative to what "success" looks like.

5. Students have opportunities to recover from challenges and failure. (students don't learn from failure, instead they learn from recovery from failure)

All of these things that have the greatest effect size can be accomplished through reflecting on grading practices, making the grading system more transparent, providing feedback, and putting in place opportunities for students to improve on past issues. We could accomplish these with traditional grading practices, but it could be easier and more natural with a change in grading practices.

Another limitation we have with our current grading system is that sometimes we have smart kids that don't do the school thing well and on the other side of the coin, we have kids that struggle with concepts but know how to do the school thing well. This can be illustrated by the table below. Student number 1 is a student who is good at school but also learns the concepts well. Student 4 is struggling with concepts and doesn't do school, so they are going to have a lot of trouble. Student 1 can probably be successful with any system you put in place. Student 4 may be unsuccessful with any system you put into place. Now, student 2 is having a hard time with concepts but does everything they are supposed to do, so their grade is probably higher than it really should be. Student 3 is a really good understanding of the concepts but won't play the school game, so their grade is probably lower than it should be. It is students 2 and 3 which we can affect the most with changing grading and teaching procedures. If we have systems in place to ensure that student 2 spends more time with what they don't know, then over time their learning will hopefully improve. If we can truly assess what student 3 knows, then it won't matter if they don't do their homework or whatever the problem is. There is something to be said about teaching a kid how to play the game of school, if for no other reason than that they need to develop skills to help them be successful outside of school. The idea of changing the grading system is about addressing the issues we have in assessing this student. Behavior-related skills should still be taught and that student should still be held accountable, they just shouldn't be punished via grading. Grading should truly show what a student knows, and consequences for behavior shouldn't enter into it at all.

So, obviously we have a problem (ok, that's an understatement). But now, what can we do about it? The idea of standards based grading has been tossed around and it does take care of a lot of the problems. It basically involves scoring students on their proficiency level on a learning standard. Proficiency is framed as a function of time and practice, so the proficiency level changes over time, over multiple assessments. Standards-based grading also takes into consideration, and inherently moderates, the effect of outliers. A grade is based on overall performance over time, without focusing on just one assessment of a particular standard. It lends itself to allowing test re-takes, not allowing a student to take a test until they are ready, providing learning experiences that do not factor into the grade (no points for homework), and any other learning-centered benefits.

But, this workshop was not about how you should convert to standards-based grading. Kevin basically focused on all of the factors of grading that are important (yes, a lot of them are addressed with a standards-based model) and how to modify your grading and entering in the gradebook to accommodate for changes that encourage learning over grade mongering. Kevin suggests that instead of thinking about changing your grading model to standards-based, think about how you can grade for learning. If it so happens to include aspects of a standards-based model, so be it.

In Practice...

When re-thinking how to approach grading, we need to first think about the purpose of grades and what grades really mean. When it comes down to it, a grade is a form of communication. It meant to communicate the status of a student's performance for the people who are not in the room with you and the student. Grades also have a way of communicating to our students what we think is important. So, we have to really think about what we want our grades to communicate to all of these people.

According to Grant Wiggins, education guru, a grade needs to be both credible and defensible. We need to define what a particular grade really means, and it is best for us to be on the same page with everyone else who is teaching that same class. The expectations of a particular grade need to be consistent (though our gradebooks don't necessarily need to be identical). Kevin suggested doing an exercise with your team or PLC where you each list your expectations for a particular grade, or what that grade means in your room class. When we did this, he had us pare down our explanation to 5 words per grade. We shared these with each other and it was pretty interesting how varied the results were!

If you have identified what you consider each letter grade to mean, you can be empowered when you face stakeholders who question your grades. You can explain "here's what it means to understand this" and "here is what they are doing." You can show "this is what an A means..." and here is the evidence I have to support this (non-A) grade..." We should keep in mind that the grade isn't the goal, but the learning is the goal. It is important to emphasize the process when talking to stakeholders, especially parents, and even the students themselves. Grading is essentially feedback for all stakeholders to allow them insight on whether a student is performing at the expectations. You want to try to change the conversation from "what do I need to do to get this grade?" to "what do I need to learn?" This is very difficult to do, admittedly, and requires a huge change in thinking for everyone. But structure of a grading system can go a long way to make this happen. I have heard that for teachers who grade in a standards based way, this kind of thing begins to happen naturally.

Kevin encouraged us not to worry about the "rules" of traditional grading. He said the rules are made up, they don't really exist, so we aren't really breaking them! Here are some things he brought up as constraints we put on ourselves and students because of the made up rules we follow:

- You don't actually have to give everyone a test at the same time--if a student isn't ready to take the test, you can wait until they are actually ready to give it to them! If a student takes a test before they are ready and they fail it, you don't really get any new information because you kind of already have all of the information that test is going to give you--that the student doesn't know the material. You could give a window of time for students to take a test in, for instance. Or you could just postpone tests on a student by student bases. Kevin mentioned that for concepts that are more important for future success in the class, you could have a more steadfast deadline for completion of a test.

- And you don't actually have to give everyone the same assessment. You have the freedom to tailor an assessment to a student so that it shows you that they learned the target in whatever form they can show that best.

- You don't have to give "points" for everything you assign. If the thing is assessing what students know, and you've given them enough time to practice and improve, your grade can really just come from assessments. Ask yourself--"will including this or excluding it affect what I am communicating about the students' learning?" Remember, grades are communication.

- You don't have to show a student their grade on an assessment right away. Kevin suggested not giving students the number but only your feedback. You can require a student to do something to improve their learning before you show them their grade.

- You can wait for quality before you grade. Kevin suggested having a separate rubric for an assignment that shows certain expectations that have to be met before you even begin to grade an assignment with the full rubric.

- You can give an assessment more than once. Give them another shot. Part of the mission and vision for our district says that students should understand that learning is not fixed, that it can always be improved. So if a student starts off the year on the wrong foot, they aren't drowning for the rest of the semester. After a fail, work with them to see that they actually learn the material and then assess them again. You could have a system in place to allow for retakes OR if a student asks for a re-take, ask them "how are you going to show me you know this before the retake?"

- ...But you can make it really difficult for them to put off your thing. You need to find a balance between making it so much work to do a re-take that they are encouraged to do more preparation up front but not so much work that it discourages them from trying again. You should create some discomfort, which is a practical consequence of slacking off originally.

- ...But you shouldn't be using a grade as a consequence. Negative behaviors such as skipping class, not studying, etc should not be met with punishment in your grading system. The consequence should be inherent in the work they are doing for your class. It should be more work to get caught up but don't penalize a student by taking points away from a grade if a student can really show mastery of a topic.

- You can grade in reverse! You don't actually have to start everyone from 100 and deduct points. Think about that first assignment you put it. Maybe it is pretty easy so almost everyone gets 100%. Everyone starts at 100% and it literally just goes down from there. Sure, you may have one or two students that could maintain 100% (with extra credit) but no one is that perfect. Everyone starts with an A and it is all about holding on to that grade. But what if you started from 0, so every assignment you entered brought a grade higher and higher? At any point, anyone can get an A. This becomes a little tricky when it is time to report progress grades. I thought about reporting a grade as what a student is on track to receive. A student may only be at 40% say, but if they continue to master at the same level, they are on track for an A. This would definitely be tricky, but could be doable. I had a colleague who was an art teacher and did something similar to this with art projects.

All of this raises the same old issue... by changing the way you are grading so drastically, there will be a big impact in a lot of other places. For one, many people will not understand your grading because it is different from what they expect and what they are used to. It will require you to educate stakeholders on your methods and rationale. Also, Kevin brought up that many colleges are starting to notice that students are expecting re-takes and that has posed a problem. The best thing you can do in this case is educate students on what they can potentially expect when they leave your room. Hopefully the methods you use in grading will actually help better prepare them for the next step because the learning process will come more naturally for them, but they could be thrown for a loop when they get to college and can't retake a test, for instance. Communication is the key to handle all of these possible problems.

A few notes on re-takes: I have been offering re-takes in some cases and I often offer some type of test correction. But, I haven't found a way that I really like yet. Here are some ideas that were bounced around on the topic of re-takes that I want to share... It was suggested that to encourage preparation for a re-take (beyond requiring a certain amount of practice) you could give back a higher percentage of points the more a student improved on their original score. Also another teacher mentioned that she allows fewer re-takes in the second semester for students she has the entire year (because there is an adjustment period for students while they are getting to know you and your assessments). For her Honors students, she doesn't allow retakes except for one during first semester. Regardless of how you handle retakes, Kevin suggested that we report this information in the notes on the grade reporting software if we are actually changing the score. Or alternatively, you could make a separate assignment for the retake and excuse students who did not do the retake.

This is a good leeway into my next section here...

Practical Applications

So maybe we are prepared to overhaul our grading system and we have educated stakeholders and everything is good until we go to enter grades in whatever grade reporting system we have and... now we have a dilemma. Grade reporting software is set up for traditional grading. It can actually be kind of tricky to manipulate it to do what we want it to do. In my district, we use Infinite Campus. We have been told that if everyone who teachers a particular class across the district can decide on a new grading scheme, it can be updated in Infinite Campus. But how likely is that to happen? We are better off figuring out a way to work around the system. As Kevin says, Infinite Campus is a one function calculator--all it can do is average. Here are some Infinite Campus hacks that will probably work for your grade reporting system too.

In your grade reporting system, you want to emphasize evidence over calculation. We have an option to enter an assignment and exclude it from grade calculation. That way, you can provide information about performance while keeping grade calculation separate. You can include an assignment that is called "present level" that you continuously update through the semester and it can be the only thing in the grade calculation. When determining the present level for a student, Kevin suggested a couple of possibilities. You could take the mode of the last 5 assignments or look overall for a trend or count the most recent evidence more heavily. We are able to set up our gradebook so that a mark can be translated into a percentage (so if you are grading on a 4 point scale, you can determine what percentage each of those points corresponds to). Here are a couple of versions that I saw being used in the examples that Kevin showed us:

Advanced

|

100

|

Proficient

|

85

|

Developing

|

70

|

Beginning

|

50

|

Insufficient Evidence

|

0

|

4

|

100

|

3.5

|

93

|

3.0

|

85

|

2.5

|

78

|

2

|

70

|

1.5

|

63

|

1

|

55

|

0

|

0

|

Note that both of these scales have a zero and this would be for students who did not turn in work. This could be marked as missing in the gradebook to communicate that the work was not received. But be careful about how you interpret the zero when you are determining a present level (remember the silliness of a zero on a hundred point scale). A colleague also mentioned that you have to be careful to enter the mark exactly as you have it entered in your scale set up or our Infinite Campus will not recognize it as a mark that needs to be converted. One more note about keeping certain assignments out of the grading--you can enter citizenship criteria this way as well and use it to assess a students citizenship grade.

One idea that my colleague and I were really excited about was that you could group your weighted categories by the thing they are supposed to learn (unit or standard) instead of type of artifact (tests, labs, assignments). This way, you can assess proficiency in that unit or standard. This seems like a nice easy step into changing your grading practices. You can still weight your artifacts by changing the point values, but you can see an overall score for the student on the particular unit. In science, it makes more sense to group in units because a lot of what we do does not build on previous work, units are often discrete. And using this system, you have the flexibility to make certain units worth more if they are heartier or are more important. My colleague and I discussed making the later units worth more (especially ones that rely on prior learning) to encourage a strong work ethic through the whole semester. Kevin also suggested that to keep it simple, within each unit you could make the assignments a group for each type of evidence and then lump all of those grades together. This would make it even easier to maintain consistent weighting for each artifact category. Using a system like this can make it a little tricky if you have a common final exam that is supposed to be worth the same for every teacher. My colleague suggested leaving that as a traditionally graded assignment and entering it at the specified percentage.

We had the privilege of seeing how some other teachers set up their gradebooks. Once science teacher had three categories; Physical Science, Experimental Design, and Communicating in Science. These were the three main things she was assessing. Physical Science was the content and included the summative assessments. Experimental design was about process and she was assessing skill. Communicating in science included things like writing, oral speaking, and visual appeal of presentations and assignments. Once you decide to break out of the mold of grouping by type of artifact, there are really so many possibilities!

Another idea that Kevin brought up was about knowing what to assess. He talked about curriculum standards vs. reporting standards. There are lots of curriculum standards and they are written for teachers, they are very specific, and they are exhaustive. Reporting standards are parent/student friendly, broader summative type standards and they are limited so there are much fewer of them. You need to decide on the subset of standards to report on. This totally comes back to the struggles of my PLC. We have definitely been working with curriculum standards and therefore our work has been very overwhelming! This summer we have been working to change this and we are making progress. Here is a diagram he drew which I think is really helpful when thinking about standards.

So basically, you have a whole lot of stuff that you teach. But, not everything you teach needs to be assessed. You are going to give feedback on a subset of all of the stuff you teach. Of the stuff you give feedback on, there is a part that you will assess. Of the stuff you assess, only some of it will contribute to the grade in the class. This is such a weird way of thinking about it because we feel like we have to give a grade for everything we assign. It definitely makes a lot of sense, though.

Extra tidbits...

Here are a couple of strategies that Kevin used during the workshop:

-We read various quotes about grading, and we wrote on a post it what is intriguing, challenging, or encouraging about the quote.

-We were given various statements about learning and for each statement, we evaluated whether current grading practices support, work against, or have no impact on that aspect of learning.

Another Resource

O'Connor How to Grade for Learning